Welcome back, DRS enthusiasts!

Welcome to the fifth issue of Bottle Bill Common Ground — a limited-series newsletter from Reloop North America highlighting evidence-based guidance for legislators, policy makers, industry, and advocates working on bottle bills. (If you haven’t read our first four issues, you can do so here.) This issue focuses on Principle #5 of the 10 high-performance principles for an effective deposit return system.

The headline I’d love to write for this issue would be “DRS is an EPR tool!” But I fear many readers might scratch their heads and click off. Let me explain why these two acronyms belong together.

The headline I’d love to write for this issue would be “DRS is an EPR tool!” But I fear many readers might scratch their heads and click off. Let me explain why these two acronyms belong together.

- Deposit return systems (DRS) — modern and effective ones — by requiring parties selling beverages to achieve the target return rate for those beverage containers, implicitly oblige them to support a redemption network centered on equity and access.

- Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) — a term coined in 1990 by a Swedish economics expert — is an environmental strategy that makes producers responsible for the entire life cycle of their products, especially takeback, recycling and final disposal. Why? To stimulate environmentally beneficial product design and an effective supply chain.

Under a modernized DRS, producers are expected to finance the system: this is key to ensuring that industry takes responsibility for the products and packaging it creates, and that municipalities and taxpayers are not left to pay the costs of managing these materials instead.

Today in the United States, there are very few examples of extended producer responsibility for packaging and paper products (PPP). We rely on the waste management sector to do what is primarily landfilling, along with some recycling and some incineration. A producer-funded DRS not only shifts the financial responsibility to those who’ve created the beverage packaging and put it out into the world, but also obliges them to manage that product through its life cycle. That gives them a reason to design and manage a container so it can be recycled in a cost effective way (hello DRS!) and the producer gets the material back to use again rather than have it wasted in a landfill.

In our earlier issue on Principle 3: 10-cent Minimum Deposit, we highlighted the importance of offering a financial incentive to consumers to return their beverage containers. Principle 5 is about offering a financial incentive to producers. And aligning that incentive to reach our target of a 90% collection rate (i.e., Principle 2).

When DRS and government recycling reforms operate purely as a stick over producers, systems perform poorly. The producer has no real skin in the game, so they put their beverages into badly designed, unrecyclable containers and care little about their return. They’re actually incentivized for low redemption and poor performance, since they receive unredeemed deposit money, especially in many Northeast DRS states.

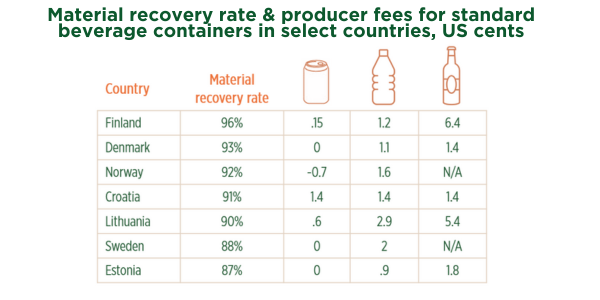

When producers finance the system, their beverage containers get redesigned and the system is managed in a way that the material is not lost but keeps flowing. Surprisingly, the more at stake for the producers, the greater the benefit for them. In fact, many of the DRS jurisdictions with the highest recovery rates also have the lowest producer fees, as illustrated in this chart.

Is this approach putting the fox in charge of the hen house? Not if one follows the high-performace Principle 10: Government Oversight and Enforcement. And that oversight of producers is informed by Principle 8: Clear System Standards & Function and Principle 9: Producer Reporting on Units Sold. (Hold tight for future issues to see how all 10 Principles are integrated to be implemented together.)

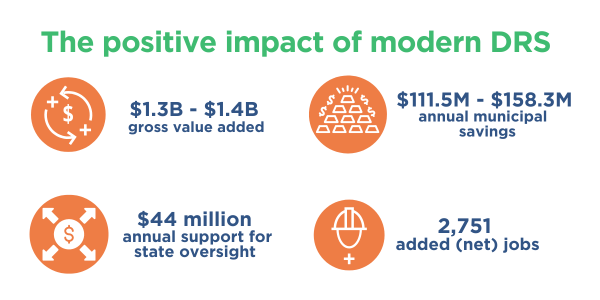

Reloop North America’s research on the impacts of DRS modernization modeled a producer-funded DRS in five Northeast states and found substantial positive economic impact across the region. Generally, the changes to regional DRSs will also have a wider benefit to Gross Domestic Product. The gross value added (GVA) of the improved system will also rise in states due to increased tax revenues from increased employment and other factors.

In New York State, transferring financial obligation for beverage packaging to the bottle bill will save New York City and municipalities across the state significant budget obligations. By Reloop’s estimate, and taking into account the full loss of revenue to material recovery facilities (MRFs), an expanded NYS bottle bill would generate cost savings of $872 million over four years (2023-2026) statewide, and $449 million for NYC alone. Over this same time period, contributions from EPR will be $0.

There are additional environmental impacts when producers fund the DRS:

- Producers will have access to more than 1.9 million additional tons of aluminum, glass, and plastic beverage containers, at a value of roughly $93 million.

- 34% of brand and material manufacturer needs for post-consumer recycled content to meet national commitments would be met just by modernizing existing DRS systems in Connective, Maine, Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont.

Ownership of this material will enable beverage brands to meet the voluntary recycled commitments they have made to consumers and shareholders, as well as comply with environmental regulatory mandates, which are expected to multiply in the years to come and have already been passed regionally in Maine and New Jersey.

Thanks for reading! We encourage you to share this newsletter widely with those who want or need to know about these principles and practices. Working together from a common ground of knowledge, we can move good bottle bills forward. Sign up here to get these blog posts as emails.